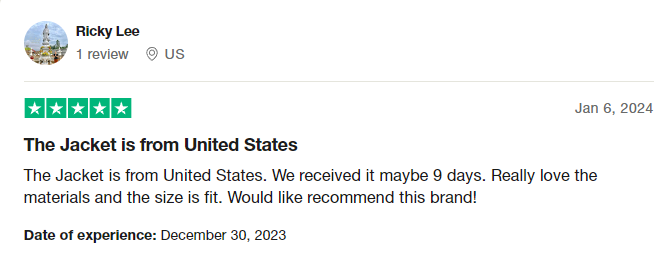

In God We Trust Guns Are Just Backup Shirt

What’s really interesting about Paul’s definition of faith for the ages, which is found in the Letter to the Hebrews, is that Paul didn’t actually write it. Hebrews was attributed to Paul by later figures such as Jerome and Augustine, who adored it. We don’t know who did write it, but one leading possibility suggested by modern scholars is a certain Apollos, who is mentioned in Acts, and who may have been a student of Philo of Alexandria. What we have here, apparently, is a Jewish Platonic philosopher who has converted to Christianity, and who takes Plato’s privileging of the unseen that extra step further. In the Greek, the word he uses is elenchus, a technical term familiar from the Platonic dialogues whose basic meaning is “ascertainment.” As Charles Freeman translates this passage in A New History of Early Christianity (2009), faith is what “makes us certain of unseen realities.” Freeman also writes that this letter possesses “a theological sophistication and coherence which is greater than anything found in the genuine letters of Paul.”3 I agree, and would add that its attribution to Paul underscores the point that the fate of religious messages depends less on their actual authorship than on their psychological resonance in succeeding ages. It would seem that Apollos (if that’s who wrote Hebrews) really tapped into something.

In God We Trust Guns Are Just Backup Shirt

Many Greek philosophers had been intensely skeptical of the gods and religion, and starting as early as the fifth century bc, we can discern a hostile religious backlash against rational inquiry in Greece. More than half a century ago, the classicist E. R. Dodds explored this phenomenon in his seminal book The Greeks and the Irrational (1951), in which he suggests, among other things, that such a backlash lay behind the Athenians’ decision to condemn and execute Socrates for impiety. Although Dodds’ book received wide approbation, his central insight—that rational inquiry and naturalistic thinking can provoke deep discomfort—has lain oddly fallow. Applying his idea to the broader sweep of history, however, suggests that the phenomenon of faith itself emerged from a similar reaction—not in mainstream Judaism, in other words, but only with the radically new splinter tradition that became Christianity as it was taken up by the larger Greco-Roman world. The very same pagan world that first shrank away from reason’s cold, impersonal touch became the earliest constituency of a loving, personal God. Once we have the story straight on who invented God and when, it’s difficult to avoid the impression that religious faith took shape as a sort of point-by-point rejection of free rational inquiry and its premises.