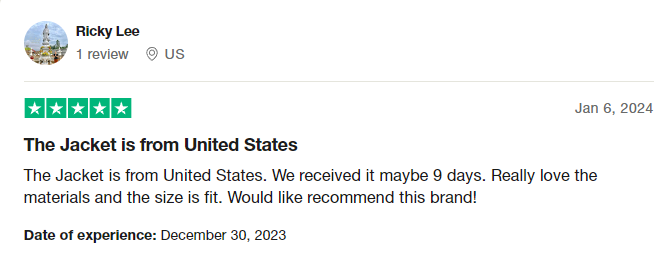

Chicken Don’t Ruffle My Feathers I Will Put You In The Trunk Shirt

But one major religious tradition—ironically, the one that gave rise to matzo-ball soup and the Sunday chicken dinner—failed to imbue chickens with much religious significance. The Old Testament passages concerning ritual sacrifice reveal a distinct preference on the part of Yahweh for red meat over poultry. In Leviticus 5:7, a guilt offering of two turtledoves or pigeons is acceptable if the sinner in question is unable to afford a lamb, but in no instance does the Lord request a chicken. Matthew 23:37 contains a passage in which Jesus likens his care for the people of Jerusalem to a hen caring for her brood. This image, had it caught on, could have completely changed the course of Christian iconography, which has been dominated instead by depictions of the Good Shepherd. The rooster plays a small but crucial role in the Gospels in helping to fulfill the prophecy that Peter would deny Jesus “before the cock crows.” (In the ninth century, Pope Nicholas I decreed that a figure of a rooster should be placed atop every church as a reminder of the incident—which is why many churches still have cockerel-shaped weather vanes.) There is no implication that the rooster did anything but mark the passage of the hours, but even this secondhand association with betrayal probably didn’t advance the cause of the chicken in Western culture. In contemporary American usage, the associations of “chicken” are with cowardice, neurotic anxiety (“The sky is falling!”) and ineffectual panic (“running around like a chicken without a head”).

Chicken Don’t Ruffle My Feathers I Will Put You In The Trunk Shirt

The domesticated chicken has a genealogy as complicated as the Tudors, stretching back 7,000 to 10,000 years and involving, according to recent research, at least two wild progenitors and possibly more than one event of initial domestication. The earliest fossil bones identified as possibly belonging to chickens appear in sites from northeastern China dating to around 5400 B.C., but the birds’ wild ancestors never lived in those cold, dry plains. So if they really are chicken bones, they must have come from somewhere else, most likely Southeast Asia. The chicken’s wild progenitor is the red junglefowl, Gallus gallus, according to a theory advanced by Charles Darwin and recently confirmed by DNA analysis. The bird’s resemblance to modern chickens is manifest in the male’s red wattles and comb, the spur he uses to fight and his cock-a-doodle-doo mating call. The dun-colored females brood eggs and cluck just like barnyard chickens. In its habitat, which stretches from northeastern India to the Philippines, G. gallus browses on the forest floor for insects, seeds and fruit, and flies up to nest in the trees at night. That’s about as much flying as it can manage, a trait that had obvious appeal to humans seeking to capture and raise it. This would later help endear the chicken to Africans, whose native guinea fowls had an annoying habit of flying off into the forest when the spirit moved them.