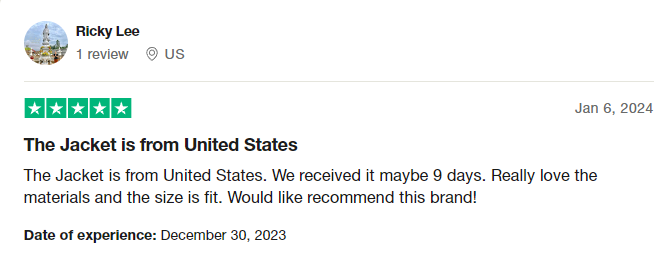

Never underestimate an old lady who loves dogs and was born in april Shirt

In the slow, hot summer immediately following Remy’s death, I languished in empty solitude. The languishing is ongoing, but it’s now occasionally replaced by other things, like noticing the rhythms of a day and of a body, which become particularly apparent when they are disruptedThe first time I worked from home without Remy, I closed my computer at the end of the day and was startled by what didn’t occur. Remy did not raise his head, stretchyawn and walk over to push his nose into my arm, silently urging Come on … it’s time to get out of here. Without his insistence, I had to think about what my next move was supposed to be. Noticing the time I spent outside. Just walking. Just being. Not looking at a screen. Ambling along the wooded trail without Remy beside me, I feel my body shrinking. For as much as Remy’s world was mine, he constantly enlarged it for meAmidst the noticing, I reflect on some of the things Remy taught me during our too-short time together, a feat surely only a dog could achieve.How to deal with danger. Remy runs ahead in the early spring evening, pausing now and again to investigate something that catches his attention. I come up beside him and as I lean down to look at an oddly shaped moss, he lets out a yip and jumps backward, pushing me aside. A snake slithers across the path just where I had been about to place my feet.

Never underestimate an old lady who loves dogs and was born in april Shirt

Aside from as hunting partners, dogs’ role as an alarm system was likely one of the main reasons early humans took so quickly to their presence. Today, dogs maintain their guardianship, alerting us to things we’ve forgotten how to pay attention to. With their protection, we are able to take risks, to be more confident navigating both human society and the natural world, which we know more about but of which we have far less physical experience.How to come to our senses. As we walk casually toward the wooded entrance of Washington DC’s Rock Creek Park, Remy finds something in a tall clump of reeds. As I approach, he wraps his paw around his treasure and, tail wagging merrily, presents it to me: the shed antler of a three-point buck.I would have passed right by Remy’s proudly procured totem that day, even though by now I should be better at seeing beyond what’s right in front of me. How many times did I watch him lift his head, pause, raise his nose and —with every whisker on his muzzle twitching to the rapid in-out, in-out of air through his nostrils—run full-speed toward something entirely unseenPhotograph by Courtney Sextonarly mammals relied heavily on their noses to gather information, and this was reflected in the structure of their brains. As species in the mammal class evolved and diverged, however, some (including primates, especially humans) became more reliant on other senses, such as sight. This, of course, came with a cost. Which explains in part why we forget that not everything we need to know about the world or our place in it can be seen.